By Saheed Ibrahim

“So, even with your disability, you are still involved in this.”

Statements like the above connotes the lived experience of persons with disabilities (PWDs) battling drug use disorder (called addiction) in Nigeria. PWDs in Nigeria face numerous social, economic, and health-related challenges, including limited access to education, employment, and healthcare services. Battling drug use disorder amidst punitive drug policies and societal neglect adds ‘salt to their injury’.

While many stories of people, especially youth, with drug use disorder have been overflogged, the voices and struggles of PWDs battling drug use disorder rarely make newspaper headlines. This story explores the complex intersection between disability and drug abuse in Nigeria, revealing how structural neglect, discrimination, and social exclusion push many PWDs into substance dependence and total silence.

Blinded by Alcohol

Umar’s journey with cigarettes, alcohol and marijuana began in secondary school in Adamawa State, where his peers influenced him.

“At first, I waited for them to finish smoking,” he said. “One day, I said to them, let me taste it and see how it is. So, the day I tasted it, from that time, I began to smoke cigarettes. Also, they are into Indian hemp and marijuana. One day, I said Let me taste the marijuana. I tasted it, and then coughed, and coughed, and coughed. So, as time went on, I began to have that urge to still go ahead and take it.”

He narrated that he continued to drink and smoke for several years afterwards until he developed visual impairment after alcohol was poured on his face during a fracas, making him battle drug use disorder and visual impairment at the same time.

He said, despite his condition, he never stopped smoking marijuana or drinking alcohol to the point that he used any little money he had to smoke or drink.

It was through the intervention of his sister, who introduced him to Pastor Jeremiah Aluwong of Lightwalk International in Kaduna, that he received his rehabilitation.

“It was difficult for me to stop… Even when I was visually impaired, I kept on taking it. So, until two years ago… I told my sister to see what I was battling. From Adamawa, she connected me with Pastor Jeremiah in Kaduna State. He has a rehabilitation centre. I underwent a recovery class for four months.”

Umar’s story is not isolated. Kunle* developed a drug use disorder due to chronic pain in his knees. The 42-year-old is a man with a mobility impairment. His body weight has surpassed what his knees could carry.

He said the drug recommended could not manage the pain, so he started taking more than the prescribed dosages until his friend recommended tramadol to him.

He said he has been managing the pain with tramadol to the point that any other drug does not work for him. “If I do not take tramadol, I won’t be able to do anything,” he said.

Kunle added that despite knowing the dangers of prolonged tramadol use, he felt trapped by the constant pain and lack of accessible medical alternatives.

Asked why he did not go to the hospital, ‘I am tired. I need someone to follow me and assist me when I go there. Aside from the fact that it is far from me, it costs a lot, and it is tiring,” he replied.

Prevalence of drug abuse among PWDs

Like Umar and Kunle, there are thousands of PWDs with drug use disorder. While national statistics on drug abuse among PWDs are elusive, the National Commission for Persons with Disabilities (NCPWD) estimated that there are over 35 million PWDs in Nigeria. A report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimated that 14.4% of Nigerians aged 15-64, approximately 14.3 million people, engage in drug abuse. Experts noted that PWDs are 40% more likely to develop substance use disorders than others.

Speaking on the prevalence of drug use disorder among PWDs, the Executive Director of Live Free Renewal Centre, David Folaranmi, noted that he had managed 16 (11 males, 5 females) PWDs with drug issues in the last year at his centre and other centres he consults.

Folaranmi

“I just finished with one right now. He had his left arm amputated because of an incident he suffered with the machine he was working with… After the operation, he started using substances. Eventually, he graduated to more serious narcotics, and this has landed him in rehabilitation for the fourth time in the last 2 years,” Folaranmi revealed.

In Ado Ekiti, the Executive Director of Disability Not A Barrier Initiative (DINABI) confirmed that there are several PWDs with drug use disorder in the state.

“I have seen PWDs taking tramadol, codeine, taking all these ‘colos’ and whatever they call their names. I have seen a lot of people. So the same way you have people drinking into a stupor, I have seen PDWs taking drinking into a stupor. That is why sometimes when you go to some states where they have rehabilitation centres, you will still find PWDs who are also battling with mental disabilities as a result of hard drugs,” he said.

While mentioning that he has rehabilitated about 300 persons with drug use disorder, including Umar, in the last four years, Pastor Jeremiah Aluwong of Lightwalk International, said he has treated seven PWDs battling drug use disorder in the last one to three years.

Pastor Aluwong

Although he drinks alcohol occasionally, Mr Oluwasola, who has a visual impairment, said that his friends, who are also PWDs, take ‘hard drugs.’ Efforts to speak to his friends after he went back to his abode in Owo proved abortive.

Disability, pain, mental health and vulnerability to drug use

PWDs abuse various drugs and substances for several reasons. While Umar succumbed to peer pressure in secondary school, Kunle became dependent on tramadol due to the pain in his legs.

A similar case to Kunle’s was highlighted by Miss Praise Akobo, the Executive Director of YieldUp Development Initiative. She narrated her encounter with a PWD with mobility impairment at a rehabilitation centre. The PWD was prescribed some drugs for chronic pain, but due to a lack of proper monitoring and support, he became dependent on the drugs and later fell into depression.

She noted that PWDs usually abuse analgesics, opioids, tramadol and codeine and can be influenced by mental health issues such as anxiety, trauma and insomnia.

Pastor Aluwong classified the drugs into stimulants, depressants and hallucinogens. He added that disability can make them more vulnerable to substance abuse. Especially disabilities that cause discomfort, pain and difficulties.

Aluwong highlighted that PWDs can abuse drugs and substances due to stress, peer pressure, genes, medical conditions and the environment they live in.

“We have people who got addicted to stuff because they had surgery, and due to some medical gaps, they got addicted to the substance. I knew a girl who had a brain tumour, had surgery, and then they exposed her to certain drugs and her brain got used to it,” he added.

He stressed that being a PWD does not stop people from abusing drugs.

According to Folaranmi, drug preference among PWDs is opioids. He explained that most PWDs with drug abuse issues do not just want to get high, but “the majority of them use depressants and opioids. Examples would be tramadol, morphine, and in some very rare cases, heroin.”

PWDs face persistent stigma and discrimination in Nigeria, contributing to their drug use disorder. A 2024 qualitative study from North-Central Nigeria revealed that families often label members struggling with substance use as “irresponsible,” leading to emotional abandonment and social exclusion. These experiences can push PWDs to seek comfort in drug use. Poverty and unemployment have also been identified as influencing factors.

A Study shows that depression and anxiety are common among PWDs and often co-exist with substance use. Many turn to substances like alcohol, cannabis, or tramadol to self-medicate.

Mr Kehinde

As mentioned by Mr Oladele Kehinde, who lost one of his legs after an accident in Lagos in 2016, he doesn’t want to die of depression.

Mr Olajide added that most PWDs live in abject poverty, and this might influence them to engage in some anti-social behaviour. He mentioned that illicit drug dealers sometimes keep their drugs with PWDs, whom law enforcement agencies will never suspect.

Olajide’s position corroborates a report by the Punch newspaper, which shows that some PWDs turn to drug trafficking or consumption as a survival strategy. The report detailed how PWDs were arrested by the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency for drug-related offences.

Beyond these factors, PWDs also engage in drug use for pleasure. Just like Oluwashola takes alcohol occasionally, Mr Kehinde said he drinks alcohol, smokes cigarettes and smokes marijuana as a socialite.

“It is not that I copy anybody. I am drinking and smoking willingly. Whenever I smoke Indian hemp, I will sit down and think about what’s next,” he said.

As Aluwong noted, PWDs also seek pleasure like everyone else.

Lack of inclusive, accessible health system worsens the crisis

In addition to factors influencing drug use disorder among PWDs, the lack of an accessible and inclusive healthcare system in Nigeria can influence drug dependency among PWDs, many of whom face several barriers to accessing treatment.

These barriers include; a lack of ramps and rails, adjustable beds, and accessible toilets in public health centres, the absence of sign language interpreters for deaf patients, psychiatric and drug use disorder services that are not adapted for those with intellectual or sensory disabilities, discrimination and neglect by health workers, contrary to the provisions of the 2018 Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities Act.

Section 21 of the Act guarantees that “PWDs shall have unfettered access to adequate health care without discrimination based on disability,” while also entitling those with mental disabilities to free medical and health services in all public institutions.

By mandating accessible public facilities within five years of the Act, the law obliges government hospitals and clinics to remove architectural barriers that currently block PWDs from seeking care.

However, the reality of Nigeria’s health system is far from this. Constant discrimination and lack of inclusive health systems have driven many PWDs with drug use disorder away from seeking help, Olajide explained.

The disability rights advocate added that many health professionals do not have the right skills to manage PWDs, and many of the health centres do not have the right infrastructure and communication personnel to support PWDs.

“You know the first thing that will come out of people’s mouths is that – so, even you, with your disability, you are still involved in this. So the moment people become judgmental towards them, it chases them away. It deters them from coming out to seek help,” he said.

Supporting Olajide, Folaranmi added that many healthcare workers receive no training in disability‑inclusive care.

He said statements like “See this one, wey get one leg, he still ‘dey smoke igbo’ make PWDs to remain silent rather than seeking help.

Lamenting the ordeal of PWDs when they visit health facilities, Oluwakemi Odusanya, a gender and disability rights advisor, said, “Some healthcare workers feel PWDs do not deserve breath or life. I have had cases of persons who are visually impaired or even had physical impairment when they are pregnant go to the hospital, and matrons or nurses around would then begin to pass out ill comments like ‘who do you like this, the person did not even try at all, even with your condition.’

“Now with such statements and communication, do you think the person will have the high esteem to go to the hospital the next time? No!”.

Oluwakemi

It costs a lot to rehabilitate

In addition to a lack of adequate rehabilitation centres to cater for the population of persons with drug use disorder, rehabilitating someone battling drug use disorder costs a lot of money, Pastor Aluwong and Mr Folaranmi explained.

“Basic rehab lasts three months,” says Folaranmi, adding that costs and duration of rehabilitation increase with the severity of dependency on drugs.”

In 2021, the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) announced plans to establish six zonal rehabilitation centres. By 2024, the agency confirmed the existence of 30 treatments and counselling facilities across the country, with over 200 million people.

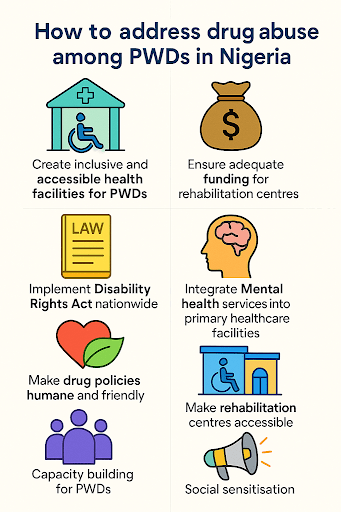

Way Forward

Addressing vulnerability through policy reform

Unfriendly, punitive drug policies deepen the suffering of PWDs caught in the grip of drug abuse.

Umar narrated that he was arrested and maltreated by security agents in Adamawa State before he became visually impaired.

“Yes, I was arrested for some of these. NDLEA, in Adamawa State, arrested me three times. They arrested me, but they did not find any evidence on me. So, because there was no exhibit with me, they did not charge me to the court. I suffered very well. I became lame. One day, I sat down and said, NDLEA will come and beat you.

Commenting, Oluwafisayo Alao-Amiola, the Executive Director of YouthRISE Nigeria, a leading organisation in public health service-delivery for young people and advocacy for drug policy reforms, emphasises the need for a comprehensive public health response to drug use control. She stated that this approach, which includes prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, research and harm reduction, will effectively address drug use among young people, especially vulnerable groups, including PWDs and also ensure improved access to services and the care they need.

Similarly, the Board Member, Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP) International, Molly Ogbodum, noted that Nigeria’s punitive drug policy fuels stigma, deters help-seeking, and worsens outcomes, especially for PWDs, who face compounded neglect.

Ogbodum recommended decriminalisation of drug use, implementation of harm reduction strategies, training healthcare providers in non-judgmental care, including affected groups in policymaking, and investing in public education to reduce stigma and promote access to health-based support.

Make health systems inclusive, accessible

Recommending solutions, experts noted that an inclusive and friendly environment will provide the needed support for PWDs battling drug use disorder.

While addressing how a lack of effective communication leads to abuse of doctors’ prescribed drugs, a Gender Equality and Social Inclusion advocate, Odusanya, identified the need for healthcare facilities to adopt inclusive communication systems, such as braille prescriptions and sign language interpreters, to ensure PWDs can understand and use medications safely and independently.

She also stressed the need for capacity building for PWDs and ensuring that they are included in the decision-making process about their well-being. Her key phrase, “nothing for us without us,” highlights the importance of involving PWDs in policy-making to ensure accessibility and measurable impact.

DINABI Executive Director, Funso Olajide, added the need for adequate funding of rehabilitation centres and collaboration between the state and non-state actors to support PWDs.

While calling for the renovation of health facilities to make them accessible to PWDs, he advised PWDs to focus on finding meaningful and respectful work rather than turning to substance abuse, emphasising that diligence and hard work can lead to a bright future.

YieldUp Development Initiative ED, Akobo, emphasised full implementation of the 2018 Disability Rights Act across all states.

She also called for the integration of disability data into national health records, training of healthcare providers on disability inclusion, and the incorporation of mental health and drug use disorder services into primary healthcare centres.

The ED of Live Free Renewal Centre, Folaranmi, called for broader, socially informed sensitisation on issues affecting PWDs, to break the stigma around drug use among them and provide inclusive spaces where they can freely express themselves.

“We must push for policy change. We must speak up. We must speak up for people with disabilities. In rehabilitation centres, there should be availability. There should be room for PWDs. Rehabilitation centres, for instance, should have ramps,” he added.

He advocated for the establishment of help desks at primary health centres to support PWDs struggling with drug use.

Graphics with ChatGPT by Saheed Ibrahim

His recommendation conforms with the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendation that disability-inclusive services should be integrated into primary healthcare systems, stressing the removal of physical, communication, and attitudinal barriers to service access, and the training of health professionals to identify and support substance use disorders among PWDs.

Similar recommendations were given by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), which mandates equal access to healthcare services, including mental health and drug rehabilitation, for all PWDs, with key provisions including the elimination of discrimination in healthcare, promotion of community-based rehabilitation (CBR) models that integrate health, education, and social support, and establishment of inclusive and accessible rehabilitation centres.

UNODC and the World Bank Disability Inclusion and Accountability Framework stress the inclusion of PWDs in national treatment plans, support for anti-stigma campaigns and public education, development and social protection programmes, tailored mental health and drug use disorder services supported by disaggregated data, and empowerment of Disabled Persons’ Organizations (DPOs) to contribute to policy and programme design.

Aluwong admonished proprietors of rehabilitation centres to think beyond profit, stressing that most persons with drug use disorder are not happy with their entrapment.

This story was sponsored by YouthRise Nigeria as part of the Media Fellowship on Ethical Reporting and Substance Use.